Invisible to Whom?

Selections from the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive

Exhibition flyer for Invisible to Whom? Selections from the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive. The exhibition is on view on the 1st floor of the University of Chicago's Regenstein Library, from February 12th-June 30th 2025.

In response to Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man, author Toni Morrison posed a profound question: “Invisible to whom?” Morrison challenged the idea of the Black protagonist’s “invisibility,” arguing that it reflected a worldview shaped by white supremacy. This exhibition rejects the white gaze, celebrating the powerful and profound connections that emerge when Black people see and affirm one another.

Robert A. “Bobby” Sengstacke (1942–2017) was a prolific photographer who devoted over half a century to chronicling Chicago’s cultural and political landscape. Best known for his work with the newspaper, The Chicago Defender—where he also served as editor—Sengstacke was pivotal in visually documenting the city’s Black community. This selection of photographs reflects his deep compassion and tenderness for his people, inviting us to reimagine what it means to see and be seen in a racially stratified world, while underscoring the power of controlling our own narratives and representations.

Curated by Rashieda Witter, this exhibition is made possible through the generous support of the Black Metropolis Research Consortium, Myiti Sengstacke-Rice, Chicago Defender Charities, UChicago’s Visual Resources Center, the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, the Terra Foundation for American Art and the Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation.

Robert A. Sengstacke, Bud Billiken Parade, 1966 -1968. Courtesy of the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive and Chicago Defender Charities. ©Myiti Sengstacke-Rice

When Black People Gather

The Sengstacke Archive is a testament to his role as a sincere chronicler of his community. His images provide evidence of his omnipresence at Chicago’s most significant community gatherings, including the annual Bud Billiken Parade. Now the largest African American parade in the United States, the Bud Billiken Parade began in 1929. It is named after a fictional character created by Robert S. Abbott, founder of the Chicago Defender newspaper. Bud was a mythical hero who became a symbol of pride, happiness and hope for Black residents during the Great Depression, and a procession bearing his name was suggested by David Kellum, co-founder of the Defender. Decades later, the parade is still a celebration of the "unity in diversity for the children of Chicago" as Kellum envisioned. Sengstacke was Abbott’s grandnephew and eventual photojournalist and editor-in-chief of the Defender, so his participation in and documentation of the parade was a natural progression. As seen in this section of images, Sengstacke captured the breadth of Black joy at this event, focusing on people with gestures and postures of pride.

The other procession photographs featured here are from a 1969 Black P Stone Rangers (later known simply as the Blackstone Rangers) march on 63rd Street on the South Side of Chicago. Widespread media representation of the notorious street gang reduced them to solely being violent, corrupt, and exploitive, while others recognized their position as a force of social activism within their community. Through Sengstacke’s lens, we get to witness their full humanity. With his camera, he preserved the full spectrum of Blackness(es), ensuring that the spirit and self-determination of the people live beyond any limiting stereotypes.

Robert A. Sengstacke, Black P Stone Rangers March On 63rd Street, 1969. Courtesy of the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive and Chicago Defender Charities. ©Myiti Sengstacke-Rice

Robert A. Sengstacke, Black P Stone Rangers March On 63rd Street, 1969. Courtesy of the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive and Chicago Defender Charities. ©Myiti Sengstacke-Rice

Robert A. Sengstacke, Bud Billiken Parade, 1966 -1968. Courtesy of the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive and Chicago Defender Charities. ©Myiti Sengstacke-Rice

Robert A. Sengstacke, Untitled, Cabrini Green, late 1960s. Courtesy of the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive and Chicago Defender Charities. ©Myiti Sengstacke-Rice. Similar to the limited perceptions of the Black P Stone Rangers, Black communities who lived in public housing projects faced similar degradation. Cabrini-Green is perhaps Chicago's most notorious housing project, with frequent reports of how crime and neglect created hostile living conditions for many residents. Sengstacke's documentation presents a counter-narrative by offering a refreshing image of a celebratory arts and cultural festival that took place on the property.

The Wall of Respect

Sengstacke’s documentation of the famed Wall of Respect is yet another instance of his consistent presence in community. Chicago’s Wall of Respect was a groundbreaking public mural created in 1967 on the South Side by the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC). Featuring portraits of Black icons like Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, and Gwendolyn Brooks, it celebrated Black pride, activism, and artistic expression during the Civil Rights Movement. Sengstacke played a key role in documenting the mural’s creation and impact, preserving its legacy through his photography. What’s unique about his perspective of the cultural landmark is that he depicts the various ways in which the community interacted with the mural as a congregation space for friends, family, and shared moments of fellowship. His images helped amplify the mural’s message of empowerment and resistance. Though destroyed in a fire in 1971, the Wall of Respect ignited a national mural movement, and its influence continues to resonate today.

Robert A. Sengstacke, Spectators Watching the Painting of the Wall of Respect, 1967. Courtesy of the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive and Chicago Defender Charities. ©Myiti Sengstacke-Rice

Robert A. Sengstacke, People at the Wall of Respect, 1967-1970. Courtesy of the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive and Chicago Defender Charities. ©Myiti Sengstacke-Rice

Robert A. Sengstacke, Spectators Watching the Painting of the Wall of Respect, 1967. Courtesy of the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive and Chicago Defender Charities. ©Myiti Sengstacke-Rice

Robert A. Sengstacke, People at the Wall of Respect, 1967-1970. Courtesy of the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive and Chicago Defender Charities. ©Myiti Sengstacke-Rice

Art & Culture

Black artists have long used creative expression as a means of resistance, self-definition, and empowerment - the history of which is reflected in the Sengstacke archive. He orbited Chicago’s pulsating artistic atmosphere, creating portraits of the city’s stars and rising luminaries. This selection of images captures the constellation of Chicago’s creative souls in their studios, at exhibitions, and other places in between and beyond. Two events of note included here are the 1972-73 Black Esthetics Art Show and the 1967 theatrical production, Opportunity Please Knock.

Robert A. Sengstacke, Robert (Earl) Paige at his Carriage House Studio, 536 E. 50th Street, undated. Courtesy of the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive and Chicago Defender Charities. ©Myiti Sengstacke-Rice.

Paige is an American multi-disciplinary artist and arts educator working across textile design, painting, collage, and sculpture based in Woodlawn, Chicago, where he was born.

Robert A. Sengstacke, Nathan Wright studio portrait, 1976. Courtesy of the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive and Chicago Defender Charities. ©Myiti Sengstacke-Rice.

Wright is a largely self-taught painter whose work blends abstraction and hyperrealism. Wright attended Chicago’s DuSable High School, where he studied art with Dr. Margaret Burroughs.

Black Esthetics

Originating in 1970 as a celebration of African American culture, heritage, and artistic contributions, Black Esthetics was a collaboration between local artists and key figures from the Chicago Defender, including Sengstacke. It embodied the era’s cultural pride through juried art exhibitions and dynamic performances in music, dance, and theater. In 1984, it was rebranded as Black Creativity, marking a new chapter in its evolution. It still takes place annually at the Griffin Museum of Science and Industry.

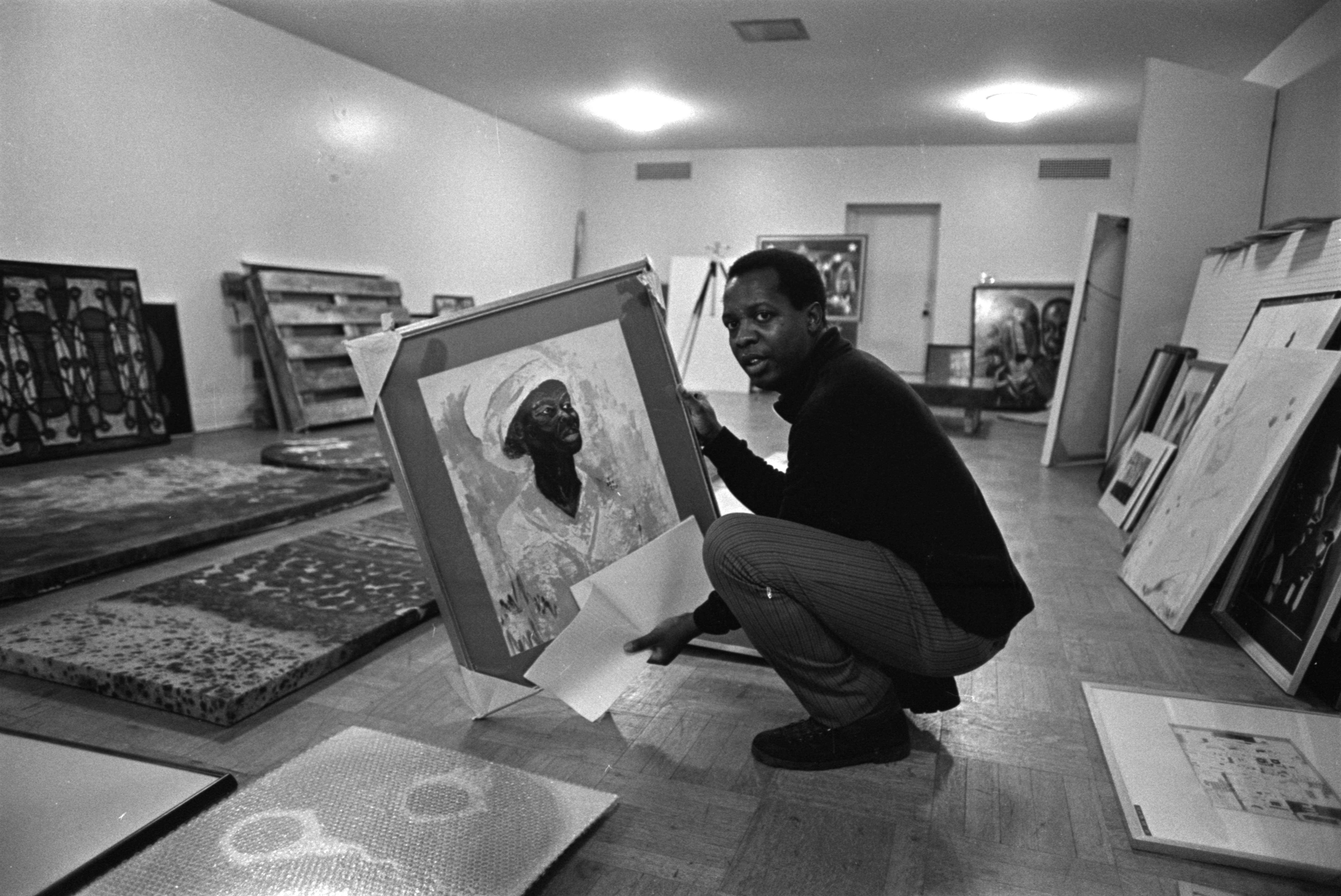

Robert A. Sengstacke, Douglas Williams at the Black Esthetics Exhibition, 1972-73. Courtesy of the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive and Chicago Defender Charities. ©Myiti Sengstacke-Rice.

Williams (1939-2019) was a sculptor and community artist who was a former director of the South Side Community Art Center. He was also a co-founder and curator of Black Esthetics.

Robert A. Sengstacke, Black Esthetics Exhibition, 1972-73. Courtesy of the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive and Chicago Defender Charities. ©Myiti Sengstacke-Rice

Opportunity Please Knock

In 1967, Chicago artist Oscar Brown Jr. collaborated with members of the Blackstone Rangers, the previously mentioned local gang, to create the musical revue Opportunity Please Knock. Performed at the First Presbyterian Church, the show attracted approxamately 8,000 attendees in its initial weeks, showcasing the talents of teenagers who previously lacked such opportunities. Brown aimed to provide an alternative to gang activities, recognizing the immense talent within the Black community. This collaboration challenged prevailing perceptions of gangs, highlighting their potential for positive community involvement.

Robert A. Sengstacke, Opportunity Please Knock, 1967. Courtesy of the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive and Chicago Defender Charities. ©Myiti Sengstacke-Rice

Robert A. Sengstacke, Opportunity Please Knock, 1967. Courtesy of the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive and Chicago Defender Charities. ©Myiti Sengstacke-Rice

Final Thoughts

Sengstacke’s images are more than mere documentation—they are declarations of presence, pride, and power. His lens did not seek to define Black life but to honor its boundless complexity, joy, and resilience. In every frame, he affirms that visibility is not granted by external forces, but forged through the act of seeing and being seen by one another. His archival collection stands as both a mirror and a monument, reflecting a people in motion—undaunted, self-determined, and luminous. Through his work, the Black gaze is not just reclaimed; it is celebrated, immortalized, and made undeniable.

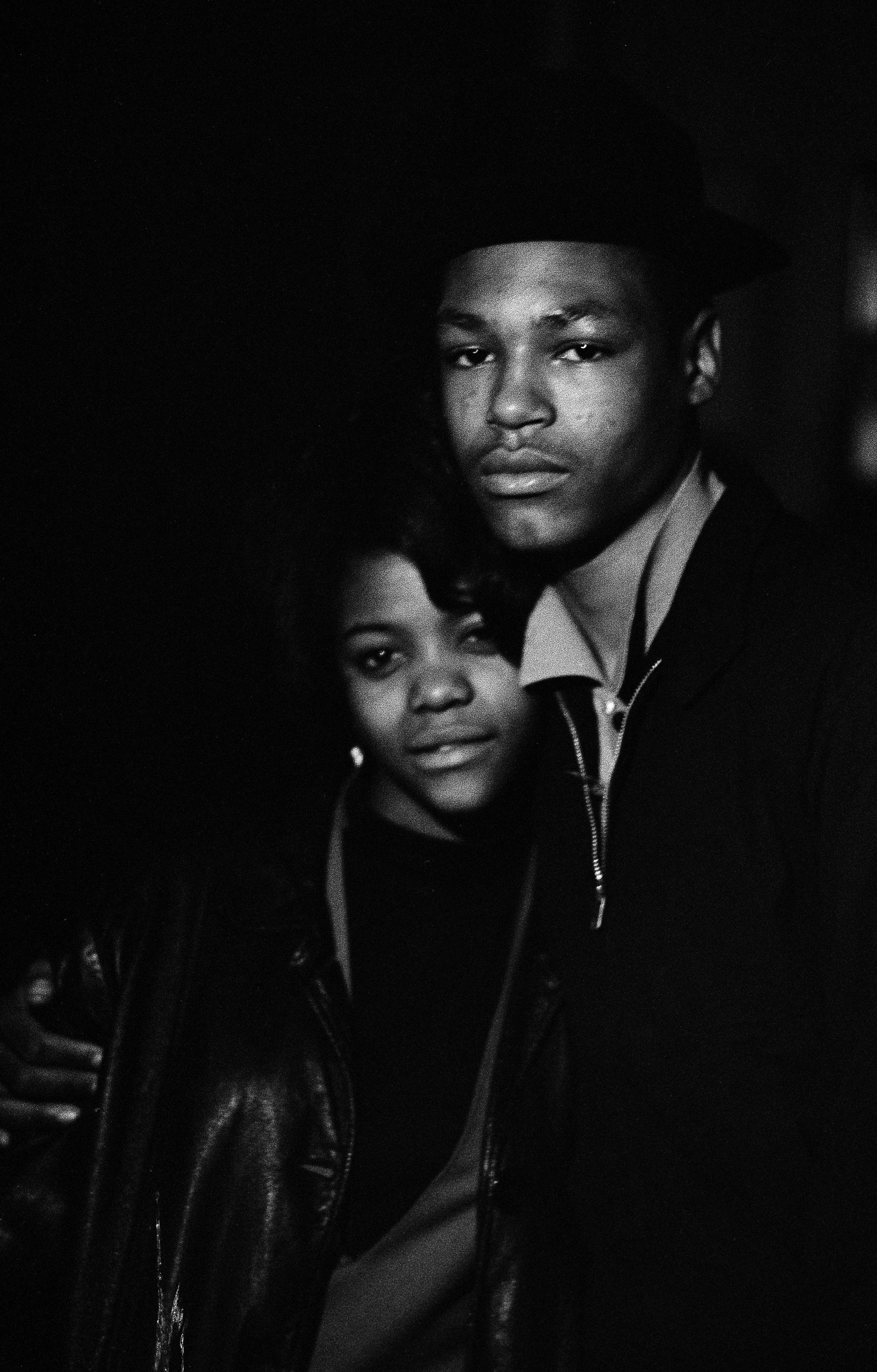

Robert A. Sengstacke, Untitled, Chicago 1965-1975. Courtesy of the Robert A. Sengstacke Archive and Chicago Defender Charities. ©Myiti Sengstacke-Rice

References

Als, Hilton. "Ghosts in the House." The New Yorker, 27 Oct. 2003, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2003/10/27/ghosts-in-the-house.

Alkalimat, Abdul, Rebecca Zorach and Romi Crawford (2017). The Wall of Respect: Public Art and Black Liberation in 1960s Chicago. Northwestern University Press. Retrieved from https://nupress.northwestern.edu/9780810135932/the-wall-of-respect/

Contreras, Ayana (2012, January 4). Opportunity, Please Knock Chorus: Oscar Brown Jr.’s Collaboration with the Blackstone Rangers. Retrieved from https://darkjive.com/2012/01/04/opportunity-please-knock-chorus-oscar-brown-jr-s-collaboration-with-the-blackstone-rangers/

Bud Billiken Parade. (n.d.). About. Retrieved from https://www.budbillikenparade.org/about

Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago. (n.d.). Black Creativity. Retrieved from https://www.msichicago.org/education/creativity-and-innovation/black-creativity